The Maskelli Maskello formula is one of the most common magical incantations of the ancient world. We find it in love spells, coercion spells, curses and invocations, it can stand on its own as well as be mixed into other strings of voce magicae. The widespread use of the formula within the magical papyri and on other magical material (curse tablets, etc.) speak to a very ancient point of origin.[1] Indeed, as with the famed Ephesia Grammata, this formula may also share a link to the Idaean Dactyls of the pre-olympic mythological age.

The formula also appears to be associated with the goddess Ananke, whose name precedes Maskelli Maskello in five spells of the PGM.[2] Ananke is the personification of destiny, fate and necessity, and she is later equated with the Roman goddess Necessitas. Thus, in the English edition of the PGM, Betz translates the proper Greek name of the goddess Ἀνάγκη to the Romanized “Necessity,” for example in PGM CI. 1-53, “I conjure you by the mighty Necessity, MASKELLI MASKELLÔ…”[3][4] Ananke’s role in the popular tradition and especially in the magical papyri is primarily as a goddess of death.[5] It is through this chthonic role that she is conflated with Hekate and indeed in PGM IV. 2785-2890 it is Hekate who is directly invoked by the formula… “Come, Hekate, of flaming council, I invoke you with these incantations. MASKELLI MASKELLÔ…”

The various renditions of the formula in the magical papyri are listed in the table at the end of this post. From these we derive a complete version of the formula that is very similar to what Betz identifies in the glossary of his edition of the Greek Magical Papyri.[6]

μασκελλι μασκελλω φνουνκενταβαωθ ὀρεοβαζάγρα ῤηξιχθων ἲπποχθων πυριπηγανύξ

MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhNOUNKENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGRA RÊXIChThÔN HIPPOChThÔN PYRPÊGANYX

Despite being classified as an untranslatable string of “barbarous” words, possible meanings can be extrapolated by looking at the linguistic and etymological roots of the seven vox magicae. For example, μασκελλι μασκελλω (maskelli maskellô) contain the root Maskil that is the phonetic spelling of the Hebrew word משכיל. This translates to ‘song of wisdom’ or ‘psalm’ and is indeed the title word of thirteen of King David’s Psalms. While it is of uncertain origin it is undoubtably understood to denote the imparting of wisdom or knowledge, as in the name Maskilim given to the scholars of the Haskalah movement of Jewish intellectualism. Identifying a magical formula as a ‘song of wisdom’ or something that imparts knowledge is a rather logical association. As we will come to see, the notion of it being a song or form of music or poetry resonates quite deeply with the legends of the Dactyls and the goetic elements of western magic.

Similarly within the word φνουνκενταβαωθ (Phnounkentabaôth) we find roots that shed light on a possible meaning. According to Gerald Mussies, the use of Phnoun in the context of the magical papyri signifies ‘the abyss’ (Egyptian pt.nun) over the phonetic name of the Egyptian deity Nun; personally, I don’t believe that these meanings are mutually exclusive.[7] The Greek root Κεντ (Kent) signifies something that stings or pricks, such as in words as κεντρίης (‘prickly’), κεντρόω (‘having a stinger’) and κεντρον (any sharp point). The suffix αβαωθ is commonly found in the name of Gnostic and Hebrew deities such as Sabaoth and Yaldabaoth. While meanings of ‘chaos’ among others have been proposed for the suffix, Gershom Scholem suggests its use in the magical literature is generally as an abridged form of Sabaoth, a Gnostic archon and also the Hellenized form of the Hebrew word for “hosts” as in יהוה צבאות (“Lord of Hosts”).[8] We can thus arrive at a possible meaning for the enigmatic φνουνκενταβαωθ as either a deity with dominion over the stinging hosts of the abyss, or as the stinging hosts themselves emerging from the abyss.

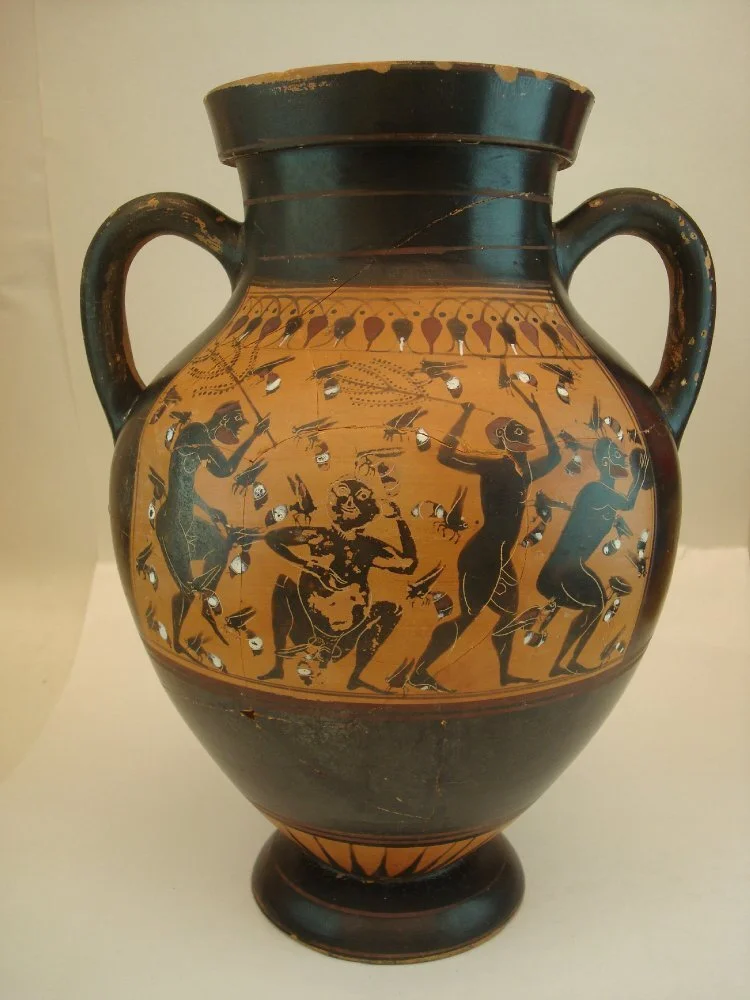

Stinging Hosts of Bees protecting the Dictean Cave depicted on Greek pottery

The idea of an underworld host of stinging entities resonates very strongly with the mythological role of bees in the Hellenic world. From the earliest times bees were connected to sacred caves (especially the Dictean cave of the Idaean Dactyls) as well as mantic and goetic practices. The oracle of Trophonios was said to have been revealed to the Greeks via a swarm of bees, and the ghosts and spirits of the dead where often described as these insects.[9] Of course the chthonic nature of bees extends to their production of honey – one of the staple offerings to the spirits of the dead and gods of the underworld. Therefore, the imagery of a host of stinging insects emerging from the abyss or underworld would have been a very relevant and symbolically important motif within the magical, oracular and necromantic traditions of the Hellenic world. For those interested in examining the topic further, I suggest Daniel Ogden’s Greek and Roman Necromancy and Bernard Cook’s article The Bee in Greek Mythology.[10]

The next vox magicae, ορεοβαζαγρα (Oreobazagra) also appears in curse tablets as an epithet of Hekate.[11] The prefix ορεο signifies mountains as in ορεομηκης (‘mountain-high’) or ορεοπολος (‘haunting mountains’). βαζαγρα (Bazagra) doesn’t mean anything; however, separated out as βαζα and γρα yields an interesting angle of interpretation. Bazo means to ‘speak’ or ‘say’ and gra – rather graa – is a an obscure word that appears in Greek lexicons to describe a type of water serpent from the Indus delta, possibly a Hellenized form of the Sanskrit grãha. Βαζαγρα could thus be a magical word signifying ‘speaking serpent’, specifically one originating in the east. Speaking serpents appear throughout Greek mythology as the oracular spirits of dead heroes, Python at Delphi being only one of many examples.[12] Perhaps the reference here is to an oracular mountain shrine of a hero with eastern origins. I should mention that I have seen this epithet translated as “of the mountain of bards”, though I have not been able to find the reference. Given the discussion here I suggest something closer to ‘of the mountain of oracles’.

The final three words of the formula all have direct translations and provide an invaluable context to the potential origins of this magic phrase. ῤηξιχθων (rêxichthôn) is an epithet signifying ‘earth-breaker’ or ‘one who busts forth from the earth’. ἲπποχθων (hippochthôn) is literally ‘earth-horse’ or ‘earth-mare’ and πυριπηγανύξ (pyripêganyx) means ‘lord of the fount of fire’. While these epithets are all in-line with how Hekate is represented in the PGM,[13] I believe that they may in fact be a reference to the Idaean Dactyls and not to a specific deity.

Indeed, the Dactyls are reputed to have ‘burst forth from the earth’ when the Great Mother Goddess plunged her hands into the ground of the sacred Dictean cave in Mount Ida (hence dactyls, ‘fingers’). These Dactyls were the first to work metal with fire and thus were revered as master smelters and blacksmiths of gold, silver, bronze, copper and iron ….they were undoubtedly the ‘lords of the fount of fire.’ They were the poets and musicians who established the mountain oracles for the Great Mother Goddess (among whose symbols was the mare or horse) and were highly skilled goetes (‘sorcerers’) who practiced epodai (‘incantations’, ‘mourning songs’) and mystery-rites. In later myths, the chthonic race of Dactyls were entrusted with the care of the infant Zeus who interestingly enough was nourished on the honey of the sacred bees of the Dictean cave, thus bringing us back to the notion of the underworld hosts of stinging insects. There is a tremendous amount of information to unpack regarding the mythology and history of these mysterious Dactyls in the development of goetic magical practices.[14]

It is perhaps no coincidence that Hekate has various connections to both the Maskelli Maskello formula and the Idaean Dactyls. Aside from the theories that she was originally a pre-Greek manifestation of the Great Mother Goddess herself, both the mythological and magical traditions speak to a direct link with these forebears of the sacred mysteries. In fact in rural areas of Asia Minor, Hekate was paired with the Phrygian god Mên (who later became associated with Apollo) and their child Acmon bore the same name as one of the Dactyls. [15] In other accounts, the female Dactyls were closely associated with the Hectaterides nymphs, in whose name we find a clear reference to Hekate and who some sources identify as her daughters.[16]

In the magical papyri the link between Hekate and the Dactyls is even more pronounced.[17] The invocation to Hekate-Ereschigal in PGM LXX. 4-25 includes the recitation of a variant of the Ephesia Grammata (ασκει, κατασκει…) and a direct reference to their chthonic mysteries: “I have been initiated, and I went down into the [underground] chamber of the Dactyls.” Through this initiation into the mysteries and practices of the Dactyls the practitioner is both protected and authorized to interact with Hekate and other chthonic forces. Perhaps the Maskelli Maskello formula was intended to operate at a similar ontological level – a goetic ‘wisdom song’ calling the ‘stinging hosts of the underworld.’ The incantation empowered – and the ritualist protected – by the magic of the Dactyls; the ancestral goetes from ‘the mountain oracle’,who ‘burst forth from the earth’ as children of the ‘earth-mare’ to become the ‘lords of the fount of fire.’

| PGM/PDM Spell | Formula as Written (ellipses indicate other nominae magicae) |

| PGM III. 1-164 | MASKELLI MASKELLÔ |

| PGM III. 410-423 | MASKELLI [MASKELLÔ]…IThÊChThÔ |

| PGM III. 494-611 | …. MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhNOUNKENTABAÔ AÔRIÔ ZAGRA RÊSIChThÔN HIPPOChThÔN PYROSPARIPÊGANYX … |

| PGM IV. 2005-2125 | … MASKELLI (formula)… |

| PGM IV. 2145-2240 | MASKELLI (formula)… |

| PGM IV. 2785-2890 | MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhNOUKENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGRA who burst forth from the earth, earth mare, OREOPÊGANYX |

| PGM IV. 3172-3208 | MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhNOUKENTABAÔ OREOBAZAGRA RÊXIChThÔN HIPPOChThÔN PYRIPÊGANYX … |

| PGM VII. 300a-310 | (MASKELLI Formula) |

| PGM VII. 417-422 | … MASKELLI (formula)… |

| PGM IX. 1-14 | MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhMOUKENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGRA RÊXIChThÔN HIPPOChThÔN PYRIPÊGANYX … |

| PGM XIc. 1-19 | MASKELLEI MASKELLÔ PhAINOUKENTABAÔ |

| PGM XII. 270-350 | MASKELLI MASKELLÔTh PhNOU KENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGRA HIPPOChThÔN RÊSIChThÔN PYRIPÊGANYX… |

| PGM XIXa. 1-54 | … MASKELLI MASKELLI PhNOUChENTABAÔTh OREOBAZARGA HYPOChThÓN …… MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhNOUKENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGRA RÊXIChThÔN HIPPOChThÔN PYRIPÊGANYX… |

| PGM XXXVI. 178-187 | MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhNOUKENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGRA RÊXIChThÔN HIPPIChThÔN PYRIPÊGANAX |

| PGM LXXXVIII. 1-14 | MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhNOUNKENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGRA RÊSIChThÔN HIPPIChThÔN PYRIPÊGANYX |

| PGM CI. 1-53 | MASKELLI MASKELLÔ PhNOUKENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGRA RÊXIChThÔN HIPPIChThÔN PYRIChThÔN PYRIPÊGANYX |

| PGM CXV. 1-7 | MASKELI MASKELÔ PhNOUKENTABAÔTh OREOBAZAGAR RHÊZIChThÔN HIPPOChThÔN PYRIPÊGANYX |

Originally published May 1, 2015 on the Voces-Magicae Website.